Before any significant design work happens on a project, you need to lay the groundwork and get everyone aligned. To do that, you need a design brief: a small-but-mighty document packed with information about your design project.

A design brief is important because it gets everyone on the same page (literally). When you’re working with multiple stakeholders—as design teams almost always are—a good design brief sets clear expectations about the project’s goals, scope, and problem. This keeps everyone focused on the core details, streamlining the design process, project management, and decision-making.

Read on to learn the fundamentals of an effective design brief, including key elements to include and a simple 3-step framework to write your own. Then, download our free design brief template to get started.

What’s in a design brief? The 8 elements to include

The goal of a design brief is to describe, holistically and at a high level, your proposed design solution for a given project. In many ways, it’s the roadmap of your design project, helping you get from initial ideation to final deliverables as smoothly as possible.

One key function of your design brief is to align all stakeholders about the project scope, objectives, and the design problem you’re trying to solve, so it’s worth being thorough. Thinking through these issues at the outset minimizes risk as your project progresses, saving you tons of time down the line.

But there’s a secret to creating really effective design briefs: user insights. To ensure your proposed design delivers an efficient, enjoyable user experience (UX), you need to draw on real user behavior data to discover existing pain points and find opportunities to proactively improve the customer journey.

Here are some key elements to include in your design brief—plus some tips on how to enrich them with behavioral and UX insights.

Ready to get started? Download your free design brief template here →

1. Foundations

The foundations part of your design brief outlines the key details of your proposed solution and the constraints within which it exists. Divide this section into subsections, such as:

Behaviors: what does your design do? You can include sketches or very basic mockups, but they aren’t always necessary. Example: add an emoji button to the message input that produces a pop-up menu of emojis.

Assumptions: what critical assumptions underlie your solution? Example: assume we’re content with a relatively small subset of emojis.

Key constraints: what non-obvious constraints shape or limit your solution? Example: licensing on emoji graphics means that unless we design our own, these will look different on different platforms.

Discarded alternatives: for additional context, what alternate solutions did you consider but eliminate, and why? Example: we considered autocomplete for emojis but discarded this idea because it requires more effort from users on a mobile device.

2. References

Include links to relevant information, such as past projects, research, competitive analysis, previous wireframes, behavioral insights about your target audience, brand guidelines—anything you think might be helpful for stakeholders.

Some useful references you can add here include

Key moments in session replays that highlight specific user behaviors

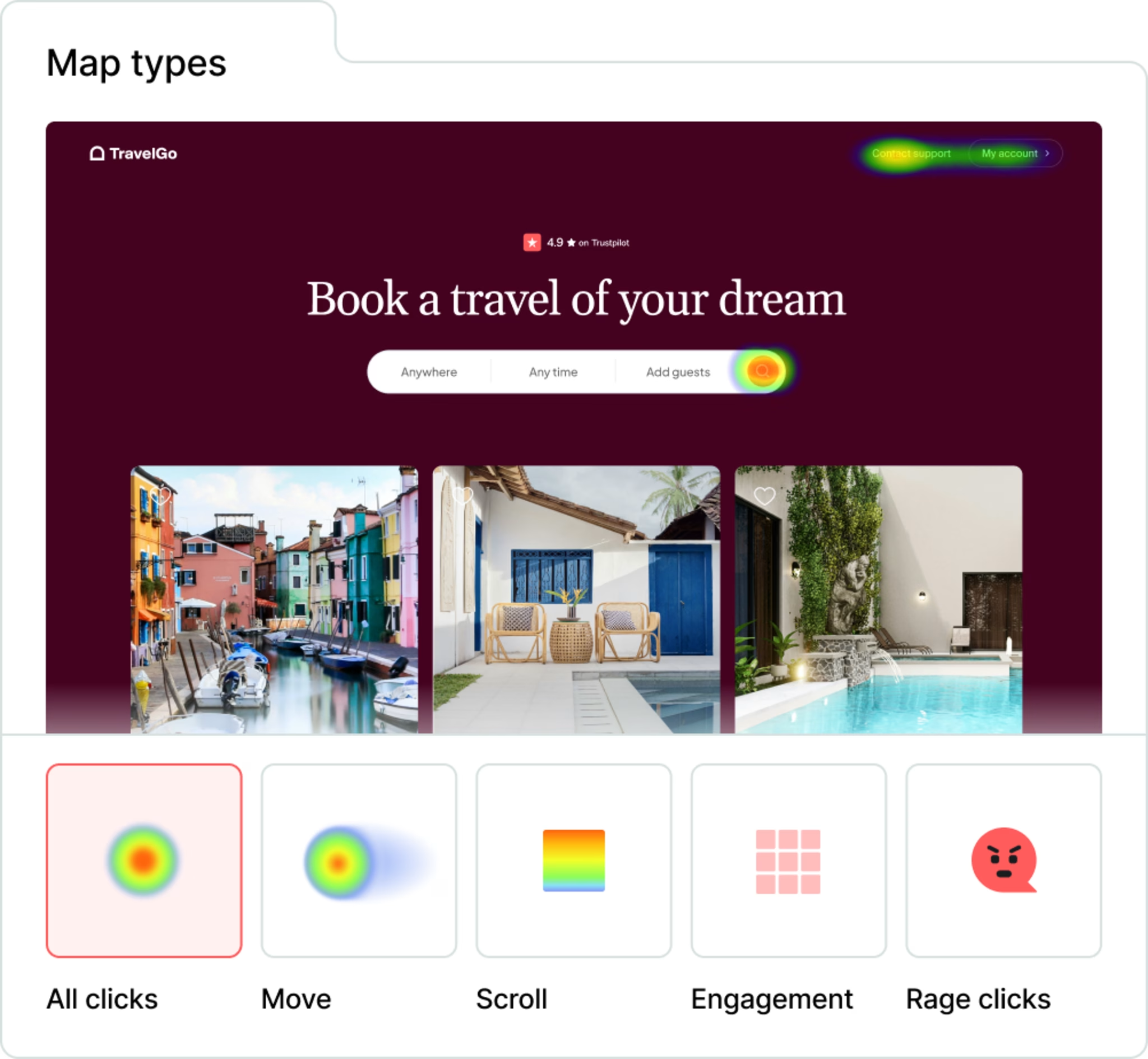

Heatmaps that show how users interact with existing or similar pages

Voice-of-Customer (VoC) feedback, like survey responses or data from user interviews, that reveal user sentiment

Up-to-date dashboards populated with key analytics for specific segments (like new users or returning customers)

Mood boards or examples of similar designs

Draw on VoC insights, like feedback, Net Promoter Score® results, or survey responses to make a convincing case for your proposed design solution

3. Noteworthy trade-offs

Design decisions come with trade-offs: project budget, quality, and scope will always impact your product design, as will other considerations like local optimization vs. systemic consistency.

This section is where you list the trade-offs in your solution that you’re aware of, and explain how you came to each decision. For each trade-off, include a description, the downside, and the reason for making it.

For example: ‘We’re replacing the existing thumbs-up button with a new emoji picker. This may reduce the number of messages sent, but we believe it will boost long-term engagement enough to be worth the risk.’

4. High-level user journeys

What are the main user journeys in your design? Describe the core journeys, but keep it simple: this should be an overview, not an exhaustive list.

Incorporate insights from your digital experience analytics platform to map these out accurately. Here’s how:

Use a customer journey analysis tool to get rich data about how users progress through your site and visualize the exact paths your highest-value users take—as well as the journeys that end in friction or drop-offs

Break down the journeys by segments for an even more granular understanding.

Then, use these learnings to inform your design and make data-driven decisions

Contentsquare’s Journey Analysis capability visualizes how users progress through your site from beginning to end, giving you valuable data for your design brief

5. Surfaces affected

Which parts of your product or site’s user interface (UI) will be impacted by this new solution? List which parts will change and how, so you can factor this into your project planning and milestones.

6. Edge cases and idiosyncrasies

Don’t try to predict every possible outcome here: instead, run through some common use cases and idiosyncrasies of your product to see how your solution will handle them. For example, consider factors like the impact of slow loading speeds, or how different roles and permission levels will interact with a feature.

Use Contentsquare’s Session Replay capability to get a deeper understanding of your edge cases and idiosyncrasies. Quickly identify friction-filled sessions with frustration scoring and AI-driven insights, then jump straight into related replays to watch how individual users were impacted by (and reacted to) these issues.

![[Visual] Session replay product shot](http://images.ctfassets.net/gwbpo1m641r7/3LL13WAqE6m1HwK774jx8Q/65fc93ad17017be0f90f682687f52760/Triggered_recording__3_.avif?w=3840&q=100&fit=fill&fm=avif)

Watch session replays to empathize with users as they navigate moments of friction

7. Not doing

Use this section to set the scope of the project. What’s not in the solution that could be, and why? This is related to trade-offs, but it also helps you to prioritize based on your core objectives. Note whether each item is something you’re definitely not doing, or if you may consider implementing it later. For example: ‘We’re not allowing custom emojis, but may enable this in the future if this feature is extensively used.’

8. Open questions

Note down questions about your design and any elements that are still under debate. These are things you can discuss with key stakeholders, experiment with, gather more research about, and explore as you develop your design.

How to write a successful design brief in 3 easy steps

With these core elements in mind—and our design brief template as a helpful starting point—it’s time to start writing your design brief. Here’s how to make it as effective as possible in 3 simple steps.

1. Clearly outline the objective for your new project

Whether you’re working on a new design or a redesign of an existing element, every good project starts with a clear goal. Why are you making this change, why now, and what do you hope to achieve?

Setting a measurable objective—such as ‘Improve UX to increase user engagement’—guides your design decisions, and helps you identify metrics you can use at the end of your project to quantify the impact of your new design.

2. Get stakeholders together early

Before you write anything down, gather all key stakeholders—your design team, product team, and product managers—and collaboratively discuss potential solutions, their feasibility, and their difficulty.

This initial conversation gives you multiple perspectives on the problem, helping you understand potential risks and challenges you might otherwise miss (including practical challenges, like resource limitations) and fostering cross-functional alignment.

3. Bring in user insights

Great design comes from empathy. As you consider the problem to be solved and fill out your design brief, consider how you can bring in user behavior insights to enhance your decision-making. For example:

Use heatmaps to see which elements of your existing design capture users’ attention, get overlooked, or lead to rage clicks

Watch session replays to understand how users from your target market behave across your site

Run surveys or user tests to get qualitative feedback from specific segments and learn about their pain points

Wherever possible, make decisions based on real user behavior data instead of hunches or assumptions. The result? More impactful, engaging, and effective final designs.

Use Contentsquare’s Heatmaps to uncover how users interact with your existing UX

Create actionable design briefs packed with user insights

Writing a great design brief isn’t about choosing the right fonts and file formats—it’s about knowing who you’re designing for, what they want, and how your proposed solution helps.

Combine our free design brief template with comprehensive behavior and UX insights to make user-centric, data-driven decisions and deliver winning designs that your customers love.

Design brief FAQs

A design brief is a short document that outlines the objectives, goals, scope, and target audience for your design project.

![[Visual] Survey retention - stock image](http://images.ctfassets.net/gwbpo1m641r7/3xD9ghYf8jbPKMEwGAJVpi/2c197fc402ee4aec10737501dd1b9291/Indoor_Workspace_with_Women_Using_Laptops_and_Plants.jpg?w=3840&q=100&fit=fill&fm=avif)