The JSONB data type lets you store BLOBs in PostgreSQL without requiring re-parsing whenever you want to access a field—and in a way that enables indexing for complicated predicates like containment of other JSON BLOBs.

JSONB makes PostgreSQL a viable choice for a lot of document store workflows and fits nicely into a startup engineering context. Just add a properties column to the end of your table for all the other attributes you might want to store down the road, and your schema is now officially Futureproof™.

Should you use JSONB to store entire tables?

There’s great material out there for deciding which of JSON, JSONB, or hstore is right for your project (further reading here), but the correct choice is often ‘none of the above’.

Here are a few reasons why.

Hidden cost #1: slow queries due to lack of statistics

For traditional data types, PostgreSQL stores statistics about the distribution of values in each column of each table, such as

The number of distinct values seen

The most common values

The fraction of entries that are NULL

For ordered types, a histogram sketch of the distribution of values in the column

For a given query, the query planner uses these statistics to estimate which execution plan will be the fastest.

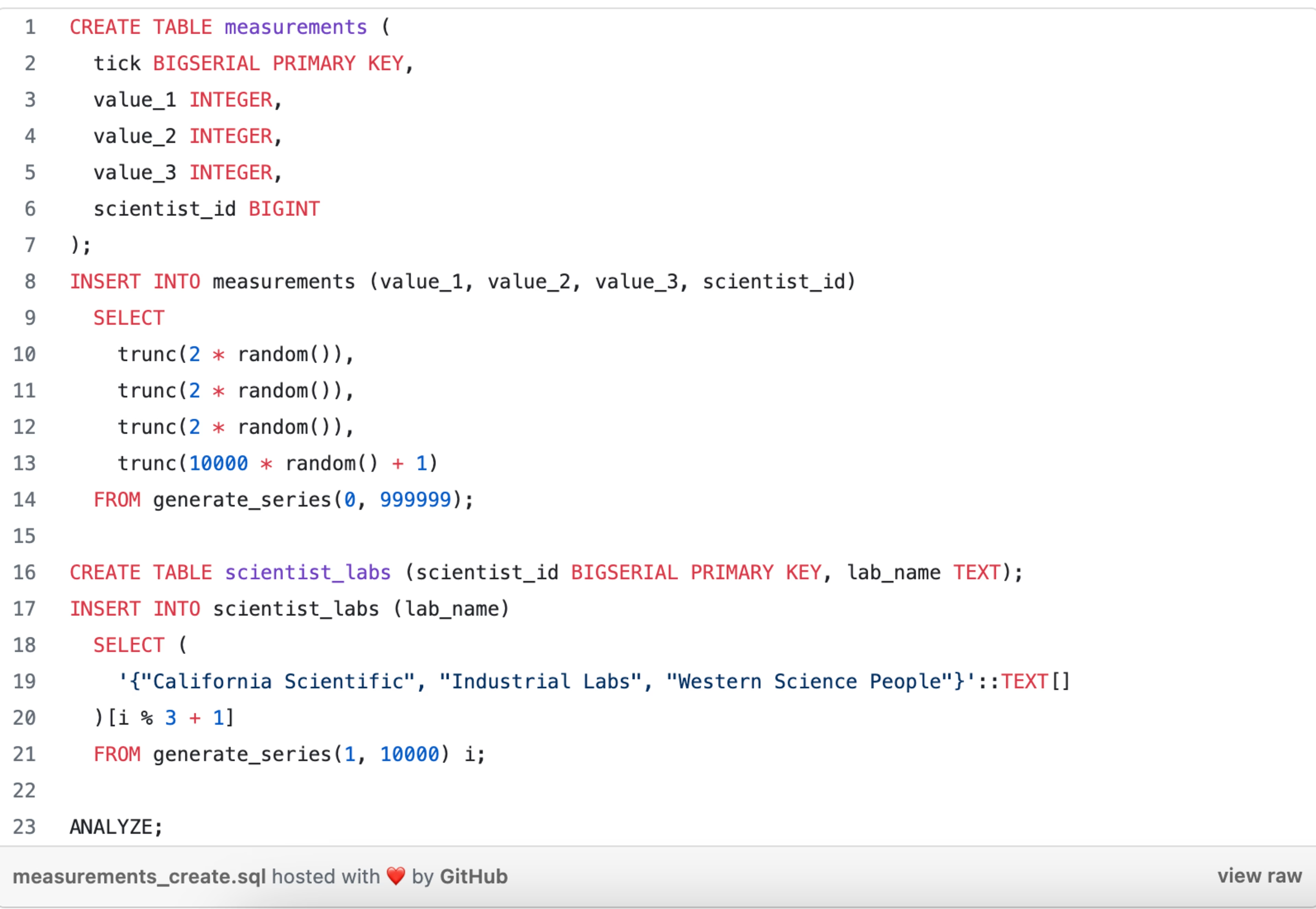

For example, let’s make a table with 1 million ‘measurements’ of 3 values, each chosen at uniform random from {0, 1}.

Each measurement was taken by one of 10,000 scientists, and each scientist comes from one of 3 labs:

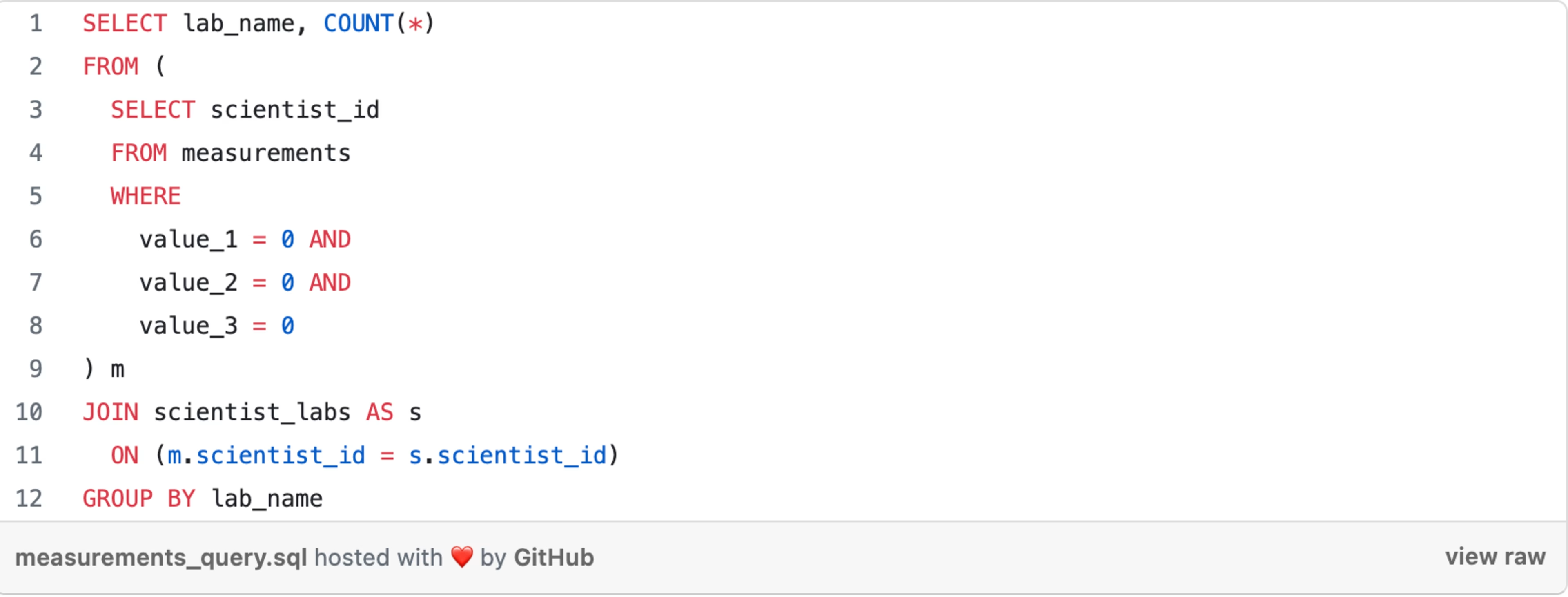

Let’s say we want to get the tick marks in which all 3 values were 0—which should be about 1/8th of them—and see how many times each lab was represented amongst the corresponding scientists.

Our query will look something like this:

And our query plan will look something like this: https://explain.depesz.com/s/H4oY

This is what we’d hope to see: the planner knows from our table statistics that about 1/8th of the rows in measurements will have value_1, value_2, and value_3 equal to 0, so about 125,000 of them will need to be joined with a scientist’s lab.

The database does so via a hash join. That is, it loads the contents of scientist_labs into a hash table keyed on scientist_id, scans through the matching rows from measurements, and looks each one up in the hash table by its scientist_id value. The execution is fast—about 300 milliseconds.

Let’s say we instead store our measurements as JSONB BLOBs, like this:

The analogous read query would look like this:

The performance is dramatically worse—a whopping 584 seconds, about 2000x slower: https://explain.depesz.com/s/zJiT

The underlying reason is that PostgreSQL doesn’t know how to keep statistics on the values of fields within JSONB columns.

It has no way of knowing, for example, that record ->> 'value_2' = 0 will be true about 50% of the time, so it relies on a hardcoded estimate of 0.1%. Consequently, it estimates that 0.1% of 0.1% of 0.1% of the measurements table will be relevant (which it rounds up to ~1 row).

As a result, it chooses a nested loop join: for each row in measurements that passes our filter, look up the corresponding lab_name in scientist_labs via the primary key of the latter table. But since there are ~125,000 such measurements, instead of ~1, this turns out to take an eternity.

(Explain.depesz is a wonderful tool for finding problems like these in your queries. You can see in this example that the planner underestimated how many rows would be returned by this subquery by a factor of 124,616.)

Accurate statistics are a critical ingredient to good database performance. In their absence, the planner can’t determine which join algorithms, join orders, or scan types will make your query fast.

The result is that innocent queries will blow up on you. This is one of the hidden costs of JSONB: your data doesn’t have statistics, so the query planner is flying blind.

And this is not an academic consideration. Storing our measurements as BLOBs causes production issues, and the only way to get around them is to disable nested loops entirely as a join option, with a global setting of enable_nestloop = off. Ordinarily, you should never do something like that.

This probably won’t bite you in a key-value/document-store workload, but it’s easy to run into this if you’re using JSONB along with analytical queries.

Hidden cost #2: larger table footprint

Under the hood, PostgreSQL’s JSON datatype stores your BLOBs as strings that it happens to know are valid JSON. The JSONB encoding has a bit more overhead, with the upside that you don’t need to parse the JSON to retrieve a particular field.

In both cases, at the very least, the database stores each key and value in every row. PostgreSQL doesn’t do anything clever to deduplicate commonly occurring keys.

Using the above measurements table again, the initial non-JSONB version of our table takes up 79 mb of disk space, whereas the JSONB variant takes 164 mb—more than twice as much.

The majority of our table contents are the strings value_1, value_2, value_3, and scientist_id, repeated over and over again.

So, in this case, you would need to pay for twice as much disk, not to mention dealing with a myriad of follow-on effects that make all sorts of operations slower or more expensive.

The original schema will cache much better or might fit entirely in memory. The smaller size means it will also require half as much i/o for large reads or maintenance operations.

For a slightly less contrived anecdote, we found a disk space savings of about 30% by pulling 45 commonly used fields out of JSONB and into first-class columns. On a petabyte-scale dataset, that turns out to be a pretty big win.

PostgreSQL allocates one byte per row for the first 8 columns, and then 8 bytes / 64 columns at a time after that. So, for example, your first 8 columns are free, and the 9th costs 8 bytes per row in your table, and then the 10th through 72nd are free, and so forth.

If an optional field is going to have a 10-character key in your JSONB BLOBs, and thus cost at least 80 bits to store the key in each row in which it’s present, it will save space to give it a first-class column if it’s present in at least 1/80th of your rows.

For datasets with many optional values, it’s often impractical or impossible to include each one as a table column. In cases like these, JSONB can be a great fit, both for simplicity and performance. But for values that occur in most of your rows, it’s still a good idea to keep them separate.

In practice, additional context often informs how you organize your data, such as the engineering effort required to manage explicit schemas or the type safety and SQL readability benefits of doing so. However, there is often an important performance penalty as well for unnecessarily JSONB-ing your data.

![[Visual] Jack Law](http://images.ctfassets.net/gwbpo1m641r7/6K99ulcVqLqKGyNZUaPiF8/145af0b27131005d862c790ddcafb3c5/Jack_Law.jpg?w=3840&q=100&fit=fill&fm=avif)

Jack has been creating and copywriting content on both agency and client-side for seven years and he’s ‘just getting warmed up’. When he’s not creating content, Jack enjoys climbing walls, reading books, playing video games, obsessing over music and drinking Guinness.

![[Visual] Content feedback - stock image](http://images.ctfassets.net/gwbpo1m641r7/3VIxae9gYdfHTaMYr25eph/96af0a02a3248b25f83d10b360591acc/Magic_Oil_-_Photo_4.jpg?w=3840&q=100&fit=fill&fm=avif)